The sprained Ankle – what does it mean

Almost everyone has heard of a sprained ankle, yet a large proportion may yet know exactly what it is. A sprained ankle refers specifically to the ligaments of the ankle and occurs when uneven ground or other external forces cause our joint to move beyond its normal range. As it is mainly the ligaments job to stabilize a joint, this often causes one or more of the ligaments to stretch. Unlike tendons, ligaments have very little elastic properties so this physical stretching can lead to microscopic tears within the ligament, thus increasing the laxity of the ligament and affecting its properties.

Ligament injuries around the ankle joint are among the most common musculoskeletal injuries seen in clinical practice. It seems no one is immune from an ankle sprain with people of all ages and walks of life suffering some form of ankle ligament sprain at some point. An ankle sprain may develop from something as simple as tripping over uneven ground while walking to the car. However, statistically speaking, people who participate in sports such as hockey, soccer, rugby and netball are at an increased risk. This is due to the quick changes of direction, sudden stopping, and pivoting manoeuvres that are required. Unfortunately, regardless of mechanism, sustaining an ankle sprain has been linked to an increased likelihood of subsequent sprains and other lower limb injuries.

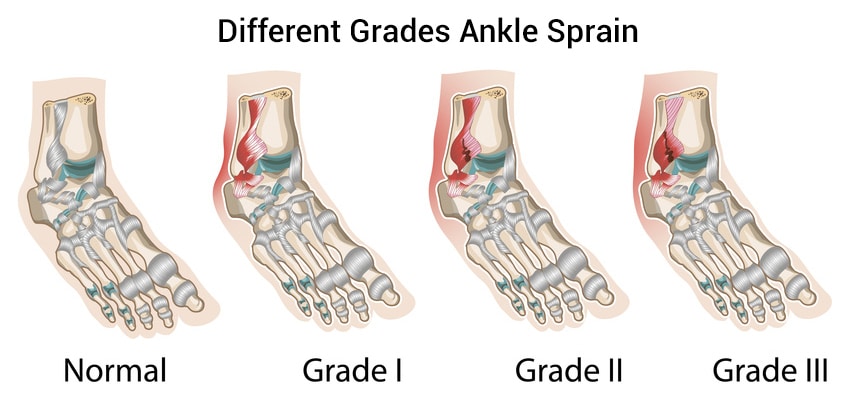

A sprained ankle can be generally classified into 3 grades depending on severity:

Grade I – implies minimal microscopic tears that don’t greatly affect the ligament stability. They are often associated with minimal swelling and little pain.

Grade II – involves a partial thickness tear of the ligament, which can affect the stability of that ligament. These can also be quite painful especially with weight bearing activities and may develop significant bruising and swelling.

Grade III– also known as a complete rupture and depending on the ligament, will often require surgical repair and lengthy rehab.

Although a common injury, unfortunately ankle sprains are not always well managed in the acute stage, and athletes will generally return to play much too soon. As a result, this often leads to a high rate of recurrence and chronic ankle laxity, both of which contribute to superfluous surgical intervention – and the complications and increased burden that come with it.

Different ligaments and their implications

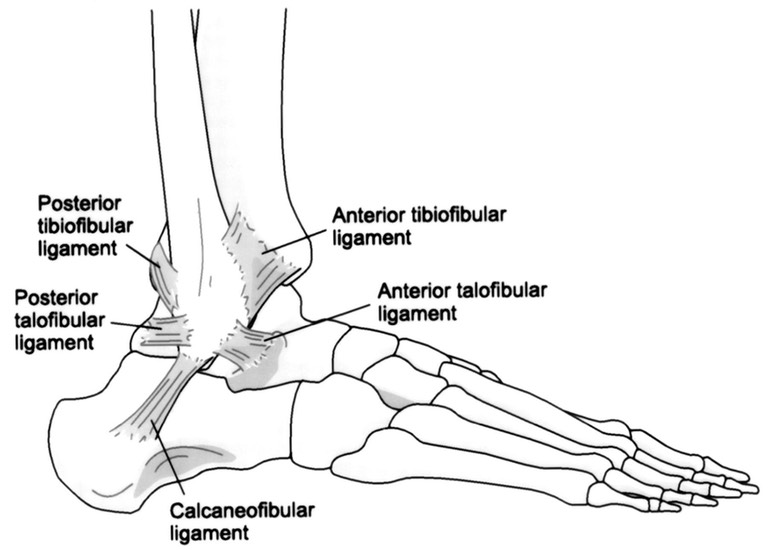

To better understand the types of ankle sprain and what they mean from a treatment perspective we need to consider the anatomy. The ankle joint is actually a combination of multiple joints that are each connected by different ligaments. The Tibia (or shin bone) is the main weightbearing bone that connects with the Fibula and the Talus to form the main Ankle joint. Looking at the lateral ankle, however, the main ligaments attach into the more lateral fibula. These include the Calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) as well as the Anterior and Posterior Talofibular Ligaments; the ATFL and the PTFL. These 3 ligaments are responsible for stabilizing the ankle against inversion injury which accounts for over 75% of all ankle ligamentous injury.

In the event of an ankle sprain, the mechanism of injury will give an important clue as to which ligaments are sprained. Generally speaking, most ankle sprains involve the lateral (outside) ligaments of the ankle. This occurs with an inversion movement, whereby we roll out over the top of the ankle. Depending on the severity of the sprain, a snap or popmay be heard at the time of injury. However, absence of an audible pop does not indicate that a complete tear has not occurred. A sprained ankle will often develop swelling and become painful with weight bearing. Bruising often follows but may take a few hours to develop so for best results your management should begin well before bruising appears.

With a suspected ankle sprain – as with most soft tissue injuries, it is crucial that you employ the CRIER principles for the first 48 hours following the injury. These are

C: Compression bandage

R: Rest from sport

I: Ice through a wet towel

E: Elevate the ankle above horizontal

R: Refer to a physiotherapist

The second R for ‘refer’ is of particular importance with ankle sprains as not all sprains are equal. Your physiotherapist will be able to assess and diagnose which particular ligaments are involved and can set you on a rehabilitation program to achieve your goals and get you back into sport in an optimized manner. The added benefit of seeing a physiotherapist while the injury is still relatively acute is that if their assessment findings indicate a more severe, full thickness tear or suspected avulsion fracture, they will be able to recommend an MRI or refer you to the appropriate sources for further investigation or treatment. Sadly, a large proportion of complete ligament ruptures or complex sprains are seen after the acute stage where their recovery and rehab may have been delayed weeks. This scenario also increases the risk of subsequent injury and/or making the initial injury worse.

Prevention is better than cure

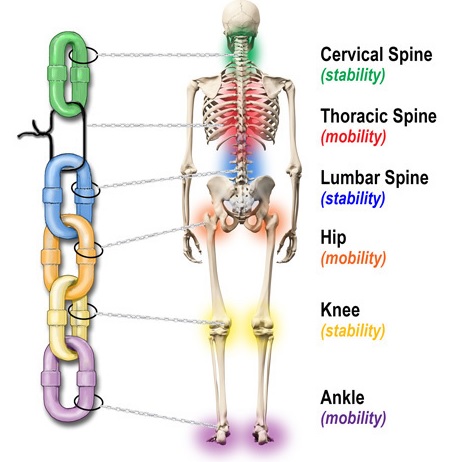

Its common knowledge that a warm up routine before exercise is beneficial in reducing the risk of serious injury. What is not so common-knowledge however is the role of stretching in this process. While holding muscle stretches, or static stretching is a great way to relieve tension and reduce muscle soreness after exercise, it should never be done as a warm up. There is a common misconception that stretching before exercise is a good way to warm up. However, research suggests that static stretching before physical exertion can actually do more harm than good. This is because a certain amount of muscle tension is protective for the joint, helping to support the ligaments. Static stretching of the lower limb muscles such as the calf, quadriceps and hamstring before sport can all increase the likelihood of ankle injury. This highlights the notion of body movement as a kinetic or kinematic chain. The different joints act together in force transfer and load handling and influence the joints upstream and downstream. Therefore, over stretching the muscles of the knee can decrease stability of the knee and increase forces going to the ankle and hip etc.

Conversely, over tight muscles can also increase the incidence of injury. To avoid this, evidence has shown that a few minutes of dynamic warm-up prior to physical exertion is important for preventing ankle injury. Dynamic refers to movement and thus requires the warm up to include movements through range. Exercises such as straight leg kicks, high knee jogging on the spot, squats and calf raises can all be used as part of a dynamic warm up. The warm up should not just focus on lower limbs, rather incorporating lower back and thoracic spine too. An optimal lumbo-pelvic region is vital for injury prevention as the lumbar spine acts as a stabilizing base for the lower limbs.

Once bitten, twice shy

As previously mentioned, suffering a ligament injury in the ankle not only increases the likelihood of reinjuring that ligament, but also increases the risk of injury to the remaining supporting structures.

If you or someone you know has a history of ankle sprains and injury there are options to allow continued involvement in sport. A proper rehab after injury guided by a physiotherapist is the best thing you can do to reduce the incidence of ankle sprain recurrence. Secondly, there is good evidence to show wearing an ankle brace, such as an ASO Ankle Stabilizer, is an excellent way of preventing ankle injuries in those with a history of ankle sprains. These are particularly useful for those who want to continue playing sport after an ankle injury.

As always, if you’d like further advice regarding the prevention of ankle sprains, or require treatment for an injury, do not hesitate to book in with your Physiotherapist.

Vatche Douzmanian

Vatche Douzmanian

Physiotherapist